The Duomatic principle concerns shareholders’ informal approval of a company’s actions. Provided that the shareholders’ approval is unanimous and given with full knowledge of what they are approving, their informal assent to a course of action, whether given prospectively or retrospectively, will be as binding as a resolution passed at a general meeting.

There has been some uncertainty under English law as to whether the informal assent of a beneficial owner (rather than the registered legal owner) of a share is sufficient to fall within the Duomatic principle. In Deakin and another v Faulding and another [2001] EWHC Ch 7, the English High Court held that a beneficial owner’s agreement to a transaction was sufficient in circumstances where the registered shareholder acted as its nominee. However, the same Court reached the opposite conclusion in Domoney v Godinho [2004] EWHC 328. In Shahar v Tsitsekkos and other [2004] EWHC 2659 (Ch), the English Court took a more holistic view and found that there was no reason why the Duomatic principle should not operate in relation to the beneficial owner of shares in an appropriate case if the facts justified it.

The application of the Duomatic principle in this context is highly relevant to the operation of BVI (and other offshore) companies. It is crucial for a company’s registered agent and professional directors to know from whom they may take instructions, in order to avoid the risk of liability for damage caused to the company through them acting on the instructions of someone without the requisite authority.

In a recent judgment in Ciban Management Corporation v Citco (BVI) Ltd & Anor [2020] UKPC 21, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (the BVI’s final court of appeal) considered the application of the Duomatic principle and offered useful guidance on its application to the question of which individuals have authority to provide instructions to a company.

Parties and background

The background to this case is a familiar one to the BVI.

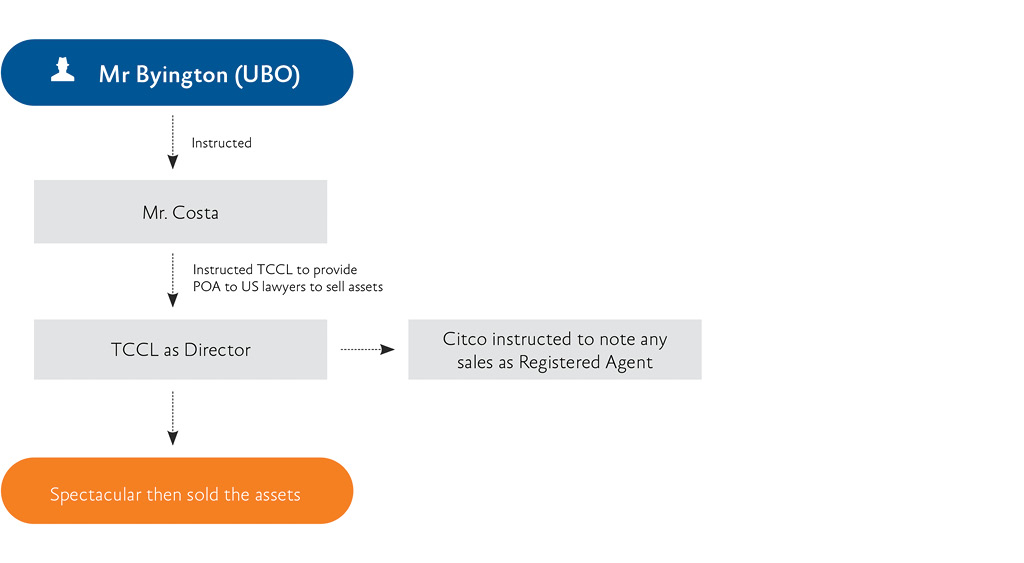

In 1997, Mr Byington told his friend and business associate, Mr Costa, to instruct a US lawyer to acquire a BVI incorporated company.

A BVI incorporated company called Spectacular Holding Inc (“Spectacular”) was purchased. Citco BVI Ltd (“Citco”) was appointed to act as its registered agent. Tortola Corporation Company Ltd (“TCCL”) was engaged to act as director. The share capital of Spectacular consisted of 5,000 bearer shares, which were held by the US lawyer on behalf of Mr Byington.

Over the next two years, Spectacular issued four powers of attorney (the “POAs”) authorising lawyers to take steps on its behalf. On each occasion Mr Costa (on behalf of Mr Byington) communicated the instructions to issue the POAs either directly to Citco, or to Citco NY, after which they were passed on to Citco in the BVI.

On each occasion Mr Costa’s instructions were followed without question, and the POA was issued by TCCL as director. During this two year period Mr Byington gave his approval for all the corporate acts carried out on Spectacular’s behalf from its acquisition up to and including the issue of the last of the POAs. There was, however, no document in evidence at trial to suggest that Mr Byington had told any of the professionals whom Mr Costa dealt with on his behalf that they could rely on his instructions; nor was there any evidence that any of them had ever asked Mr Byington for confirmation of those instructions. This was largely because Mr Byington wanted to remain out of the public eye.

A familiar structure formed:

Unbeknownst to Mr Byington, Mr Costa sent an email to Citco containing the text of a draft POA which he asked Spectacular to grant so as to authorise a lawyer to sell five parcels of land which comprised Spectacular’s only assets. The next day, TCCL passed a resolution providing for the issue of that fifth POA and executed it. Subsequently, a contract for the sale of the property was concluded between Spectacular and a purchaser.

Somewhat inevitably, Mr Byington and Mr Costa had a disagreement on account of Mr Byington owing Mr Costa money.

It was only after the first four sales of the land parcels had completed that Mr Costa contacted Mr Byington to inform him for the first time what had happened and provide a breakdown of the sums that he believed Mr Byington owed to him.

Mr Byington, unsurprisingly, did not take kindly to this and caused the fifth POA, together with the earlier POAs, to be revoked and commenced proceedings seeking to prevent registration of the sale.

Spectacular then issued proceedings in the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court in the BVI against Citco and TCCL, alleging, among other things, that TCCL had acted in breach of its tortious (and fiduciary) duty of care as a director in failing to ensure that Mr Costa had the authority to procure the grant of the fifth POA.

First Instance

The Honourable Mr Justice Bannister handed down the first instance decision on 27 November 2012 dismissing the claim brought by Ciban (Ciban effectively stepped into Spectacular’s shoes for the purposes of the litigation). He reasoned that:

- Citco owed no duty of care to Spectacular as any such duty was owed to Mr Byington, as ultimate beneficial owner.

- Even if Mr Byington had been the claimant, he too would have failed in his claim. This was largely because Mr Byington had “set up a system, upon which he clearly expected the professionals to rely, under which he remained in the shadows while Mr Costa communicated his instructions and was the point of contact. He never told any of the professionals that the system had ceased to operate or had changed – until too late”; and

- Spectacular did not have a claim against TCCL for breach of duty as a result of its failure to conduct due diligence on the sale of the assets of Spectacular, or its failure to challenge the instructions which it received regarding the proposed transaction. In reaching this decision, Justice Bannister reiterated the need “to pay the most particular attention…to the whole circumstances of the case”. In considering the background context relating to the agreement between TCCL and Mr Byington, and the previously issued POAs, he held that it was implicit in the agreement between TCCL and Mr Byington that TCCL was “not expected to exercise any independent executive functions or discretions. Its role was execution only”.

Dissatisfied with this decision, Ciban appealed to the Eastern Caribbean Court of Appeal.

Court of Appeal

On 13 February 2019, the Court of Appeal affirmed the decision of Justice Bannister. Madam Justice Blenman reasoned that Citco and TCCL were entitled to conclude that Mr Costa had Mr Byington’s ostensible authority to procure the POA.

Privy Council

The Privy Council upheld the decisions of the courts below. In holding that TCCL did not breach its duty of care to Spectacular, the Privy Council highlighted the need to consider the context within which TCCL was operating, which was that. “Mr Byington wished to be kept out of the public eye”. As such, the law should not allow Mr Byington to shift the risk which he bore with regard to the employment of Mr Costa as his agent to TCCL and to Citco.

The Board approved Mr Justice Bannister’s comment that TCCL’s role was simply one of “execution”, reasoning that due to its limited function “TCCL could not reasonably be expected to scrutinise proposed sales by the company”.

Regarding Mr Costa’s ability to issue the POAs (the ostensible authority argument), the Board noted that:

“(i) Citco BVI and TCCL were aware – for example, from the refusal of Mr Byington to sign the management agreement in November 1997 – that Mr Byington wished to remain “in the shadows” albeit that he was the ultimate beneficial owner.

(ii) Over the course of two years, dealing with four POAs, Mr Byington had given Mr Costa actual authority to give instructions (whether directly or through Citco NY) to Citco BVI and TCCL.

(iii) Mr Byington had not raised any complaints over those two years about the first four POAs (and neither had Spectacular nor Mr Stollman)”.

The Board found that manner in which Mr Byington structured his holdings in Spectacular supported Citco and TCCL’s position that Mr Costa did have the requisite authority to instruct them to produce the POAs and for the assets of Spectacular to be sold.

Helpfully, the Board also considered “whether one can apply the Duomatic principle of informal unanimous shareholder consent to ostensible authority”. It concluded that it could, reasoning that, “[I]f actual authority can be conferred informally by unanimous shareholder consent the same should apply to ostensible authority. So here Mr Byington’s informal consent to the representation by conduct, that Mr Costa had authority to instruct TCCL (and Citco BVI) in relation to the fifth POA, binds Spectacular”. Spectacular, therefore, could not be allowed to deny that it authorised Mr Costa to provide instructions to TCCL.

Dishonesty

An interesting finding of the Privy Council in this case relates to dishonesty. It was previously held that the Duomatic principle cannot be used where there is relevant dishonesty. However, the Privy Council in this case held that there was in fact no dishonesty with regard to the issue of the power of attorney (despite the underlying intent of Mr Costa to retain some of the proceeds that he considered as repayment of a debt owing to him).

The Privy Council considered that, even if there had been no cited reason, such as repayment of a debt, and Mr Costa had sought to retain the money, the principle would still apply as “the whole of Mr Byington’s set-up – and the clothing of Mr Costa with ostensible authority – was taking the risk on behalf of the company, albeit informally, that Mr Costa would use that apparent authority for his own purposes, including dishonest purposes”. This may be detrimental to any UBOs wishing to assert that their assets have been disposed of by an agent acting dishonestly in circumstances where the UBO intentionally gives full authority to that agent in an attempt to remain invisible from certain transactions.

Conclusion

This decision serves to highlight the applicability of the doctrine of ostensible authority in the context of the Duomatic principle. Claimants cannot seek to ‘shift the risk’ to innocent service providers who serve a limited function, in an effort to obtain relief from their own misjudgements.